Proposal: Guidelines

The real-world, academic model for the SCE you will complete (in your senior year) is a 25-30 page essay that we scholars publish in journals, books, and other venues, based on extensive research (an Annotated Bibliography due in the fall of your senior year) and substantial drafting and revision (the essay composed in the spring of your senior year). You have likely encountered and started to work on initial ideas in other English courses that could serve as the foundation for the SCE. But you probably don’t know it yet.

So, how do we work toward that substantial project, explore a direction before we know where we are going? There are various models scholars use to explore and develop their initial thinking/reading/writing on the way to more substantial, publishable scholarship: sometimes they’ll take the form of a conference presentation, other times a proposal for a grant or fellowship.

For this assignment, you’ll be writing a substantial proposal for future research. At 1750 words or so (inclusive of abstract), it will be on the longer end for SCE proposals in the English department, but this length is common to professional research proposals and as such will give you the space to fully articulate your research findings and your claims in relation to them.

Guidelines:

1500 words + 250 word abstract. Your project proposal should begin with a re-revised abstract summarizing your proposed project. Remember, that proposed project is essentially an academic article, examples of which you’ve been reading all semester. The body of your proposal should:

- describe the project, explaining the topic and the significance of the argument;

- place the work in the context of your field (methodological, geographical, and period-based as applicable);

- indicate how the project would contribute to that field;

- be clear about the critical theory and methodology informing your argument; and

- make sure to situate your work in relation to others. You may use *revised* portions of your literature review to do this.

For some further guidance on an Academic Proposal, consult this resource from the University of Toronto.

Proposal: Brainstorming–Particle/Wave/Field

For further development and complication of your project’s argument as it stands now, use this heuristic (in classical rhetoric: a model or structure to generate or organize thinking for an essay, argument, project, a device for invention) known as the particle/wave/field heuristic. I summarize it below by way of the rhetoric book Form and Surprise in Composition: Writing and Thinking Across the Curriculum by John Bean and John Ramage [they take the heuristic from the Young, Becker and Pike’s Rhetoric: Discovery and Change]. They suggest it as a method that helps develop an argument on a given topic by enabling the writer to switch perspective systematically.

First, take your topic X and view it as a static, unchanging entity (particle): note its distinguishing features, characteristics; consider how this entity differs from other similar things. You will know some of these details and characteristics from your research–how other critics and scholars have defined your topic in the past.

Second, view the same topic as a dynamic changing process (wave): note how it acts and changes through time, grows, develops, decays. Think of this as where your Y enters the topic: issues, questions, problems that you might pose, wanting to learn more about the topic, recognizing (from your research and review) that there are some gaps, there is more to know or do with this topic.

Third, view the topic as a Field, as related to things around it and part of a system, network or ecological environment. What depends on X? What does X depend on? What would happen if X doesn’t exist? Who loves (hates) X? What communities (categories) does X belong to? What is X’s function in a larger system? This is a way to identify critical and theoretical implications for your argument–the larger field and conversation that your study participates in, relates to (and lots of other “reverbs”), potentially revises, but also (this is what is complicated about “field”) is potentially revised by. This is your stake, your “So What.”

Where, when, how, why, and in what forms do we experience gender and sexuality in life? In literature and culture–in other words, as readers/writers/scholars in English? Much as we discussed recently with postcolonial criticism and its overlapping interest in issues of race, I propose that we interrogate how various concepts and keywords from feminist criticism, gender and sexuality studies, and queer theory speak to our experiences with literature and culture.

Where, when, how, why, and in what forms do we experience gender and sexuality in life? In literature and culture–in other words, as readers/writers/scholars in English? Much as we discussed recently with postcolonial criticism and its overlapping interest in issues of race, I propose that we interrogate how various concepts and keywords from feminist criticism, gender and sexuality studies, and queer theory speak to our experiences with literature and culture.

Psychoanalytic literary theory and criticism is by no means limited to the insights and theories developed by Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. As Lois Tyson demonstrates, a great deal comes after Freud and the classical psychoanalysis that he establishes in the early 20th century, and much of that challenges while also building upon Freud’s “discovery” of the unconscious: Jung, Lacan, French feminists such as Kristeva and others who build upon Lacan and psychoanalytic theory. It’s complex stuff, and even though I took an entire course in graduate school on psychoanalytic theory, much of it is beyond my limited powers of understanding.

Psychoanalytic literary theory and criticism is by no means limited to the insights and theories developed by Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. As Lois Tyson demonstrates, a great deal comes after Freud and the classical psychoanalysis that he establishes in the early 20th century, and much of that challenges while also building upon Freud’s “discovery” of the unconscious: Jung, Lacan, French feminists such as Kristeva and others who build upon Lacan and psychoanalytic theory. It’s complex stuff, and even though I took an entire course in graduate school on psychoanalytic theory, much of it is beyond my limited powers of understanding. Finally, the reader. After working our way through New Criticism, structuralism, and the poststructuralist critical theory of deconstruction, we finally take up a key subject in the literary experience heretofore forgotten by analysis of “the text itself”: the reader. As we saw, in a variety of ways, all three previous theories and methods of literary interpretation–from Brooks to Barthes to Derrida–focus so thoroughly on the text as object and linguistic construct that the reader (and also the author, another kind of reader, an embodied subject) seemed to matter not in the least. Even to the point of the critic’s own unimportance in the end: the text, after all, deconstructs itself. If there is no outside the text, there’s also no reader separate from the text, waiting to take it up.

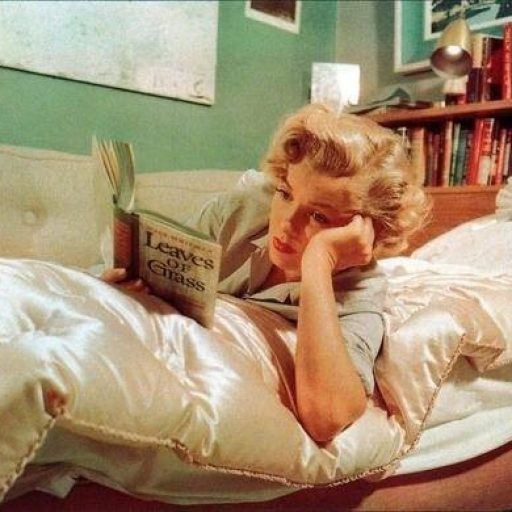

Finally, the reader. After working our way through New Criticism, structuralism, and the poststructuralist critical theory of deconstruction, we finally take up a key subject in the literary experience heretofore forgotten by analysis of “the text itself”: the reader. As we saw, in a variety of ways, all three previous theories and methods of literary interpretation–from Brooks to Barthes to Derrida–focus so thoroughly on the text as object and linguistic construct that the reader (and also the author, another kind of reader, an embodied subject) seemed to matter not in the least. Even to the point of the critic’s own unimportance in the end: the text, after all, deconstructs itself. If there is no outside the text, there’s also no reader separate from the text, waiting to take it up. That ominous phrase and concept, “the death of the author,” has long been attached to deconstruction, or deconstructive criticism. Deconstruction is a leading critical theory of a larger grouping of literary and critical theory that emerges in the 1960s and 1970s in Europe, and thrives in American academic institutions (mostly) in the 1980s and 90s. That larger grouping is known as “poststructuralism,” a phrase which in some ways overlaps with the term “postmodernism,” but not entirely.

That ominous phrase and concept, “the death of the author,” has long been attached to deconstruction, or deconstructive criticism. Deconstruction is a leading critical theory of a larger grouping of literary and critical theory that emerges in the 1960s and 1970s in Europe, and thrives in American academic institutions (mostly) in the 1980s and 90s. That larger grouping is known as “poststructuralism,” a phrase which in some ways overlaps with the term “postmodernism,” but not entirely. Is there a text in this class? That’s a famous line (and title) from reader-response literary theory, coming later in the semester. For the first two weeks of our exploration of critical theory, the answer to that question is decidedly: “yes, there is only text in this class.” Beginning with the New Criticism, one of the oldest of the critical/literary theories we will study, and then continuing into structuralism and deconstruction, scholars and critical readers focus thoroughly and rigorously and entirely on texts. Although those texts are produced by authors who live in various historical contexts and bodies, and are read by readers who also live in various and different historical contexts and bodies, New Critics, structuralists, and deconstructionists will exclude those other contexts and focus on (a refrain) “the text itself.”

Is there a text in this class? That’s a famous line (and title) from reader-response literary theory, coming later in the semester. For the first two weeks of our exploration of critical theory, the answer to that question is decidedly: “yes, there is only text in this class.” Beginning with the New Criticism, one of the oldest of the critical/literary theories we will study, and then continuing into structuralism and deconstruction, scholars and critical readers focus thoroughly and rigorously and entirely on texts. Although those texts are produced by authors who live in various historical contexts and bodies, and are read by readers who also live in various and different historical contexts and bodies, New Critics, structuralists, and deconstructionists will exclude those other contexts and focus on (a refrain) “the text itself.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.