When reading the chapter in Critical Theory Today about feminist criticism, many of the topics and key words introduced were very familiar to me. I am currently taking a course on modernist women writers, so we often discuss the subversion of traditional gender roles within the texts and how we as readers can track the progression of feminism through literature. However, while reading this chapter I realized that I have never really paid much attention to traditionally gendered terms themselves, I have only been using these terms in order to analyze a text. Especially when looking at how traditional gender roles “cast men as rational, strong, protective, and decisive” and women as “emotional (irrational), weak, nurturing, and submissive” (Tyson 81), I am interested in how gendered terms can be used to perpetuate or subvert these connotations.

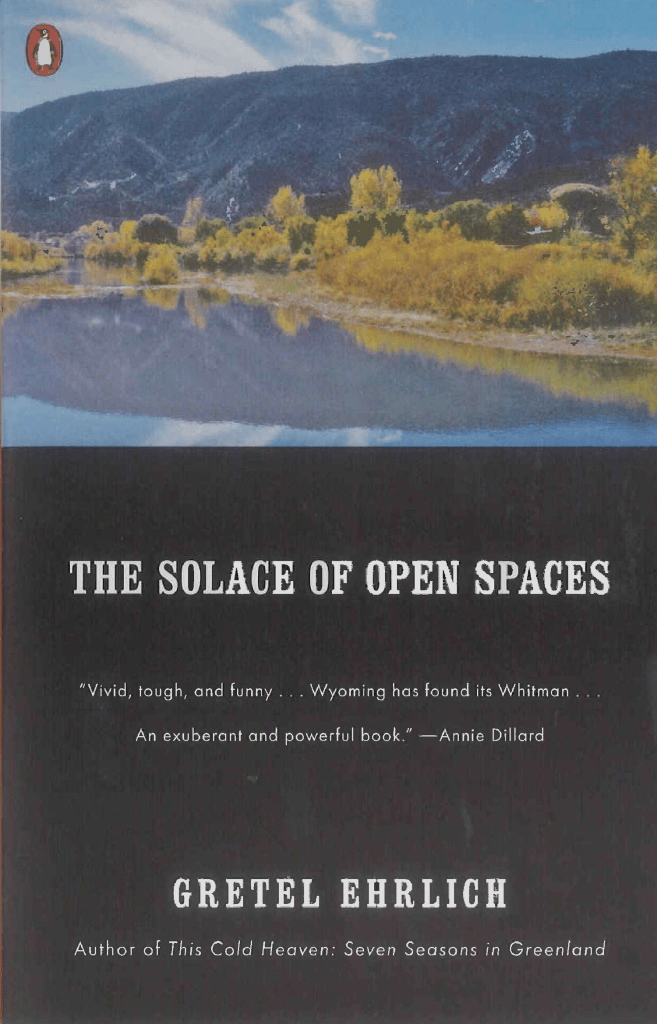

Obviously, our society functions on the basis of binaries in order to maintain some form of organization and distinction, but language in itself consists of banal words and letter that we communally assign meaning to: there is nothing inherently female or feminine about the word pink, but we use the color to distinguish between females and males at birth and then we associate the term and the color with females in all other ways. Because our society would fall apart without language, we as readers and critics cannot take the connotations and denotations of terms lightly. With this in mind, I am interested in looking at how feminist criticism can be used as a lens to view certain terms that are being used in a universally, ungendered way by literature, musicians, and even universities. This term? “Cowboy.” I will start my exploration with Gretel Ehrlich’s androgynous view of the cowboy in The Solace of Open Spaces and then move into the University of Wyoming using the tagline “The world needs more cowboys” in 2018 before tying my interrogation together with the use of the term “cowboy” in mainstream music in 2018 and 2019. With the explosion of the term “cowboy” and all the associations the word carries with it, I think that feminist criticism will allow me to see not only the progression of the term, but it will give me insight into how the term has gone through this sort of evolution. Just as how a character can subvert traditional gender roles in a text, why can’t a term subvert those same gender roles in a society?

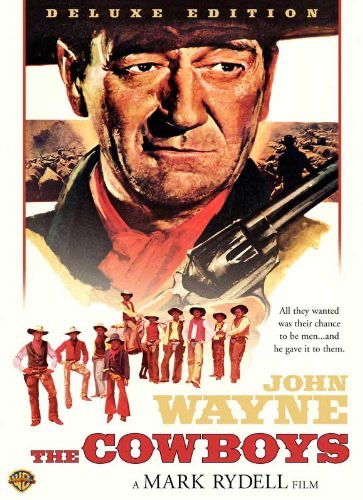

In her chapter titled “About Men,” Ehrlich deconstructs the myth surrounding the American cowboy. Instead of perpetuating the legend of the cowboy, Ehrlich explains that if the cowboy is “gruff, handsome, and physically fit on the outside, he’s androgynous to the core. Ranchers are midwives, hunters, nurturers, providers, and conservationists all at once” (51). Ehrlich’s perspective of the cowboy completely challenges the traditional view of the cowboy as hardened shell who is ruthless and capable of any task. Really, the cowboy that we associate with this term refers more to the John Wayne’s of Western cinema rather than vaqueros. Ehrlich exposes the vulnerability of the cowboy in a way that opens the term up to be used for women as well by describing the cowboy as someone who can be a midwife and a nurturer, terms that are traditionally associated with women. If we as readers look at this redefinition of the term cowboy, it is interesting to see how the term can then be used to refer to both men and women in an ungendered way.

The University of Wyoming in 2018 latched onto the tagline “The world needs more cowboys.” While many feminists criticized this phrase and its inherent “manliness,” the claiming of the term by women can also be seen as a step toward equality. Regardless of how the term is used, it is very interesting to see how one single term can come to represent something so polarizing.

Especially with a term that has such a strong connotation behind it—it instantly makes one think of wild horses and wide open landscapes and hard labor—it is perhaps not all that surprising that a few female musicians have started to use the term “cowboy” within their music and simultaneously subvert the meaning of the term while also using the traditional sense of the term to validate their work. For instance, alternative musician Mitski Miyawaki released her latest album in 2018 titled “Be the Cowboy.” As a female, Asian musician, her decision to include the word “cowboy” in the title of her album certainly is a statement. In terms of feminist criticism, this decision is ingenious: it not only defines the term cowboy to include any person of any gender, age, or race, but it also show’s Mitski’s fearlessness and power as a musician and individual. To be able to claim a term that would have excluded anyone like Mitski in the past gives her the power of the term and then some, as Ehrlich says, “To be tough is to be fragile; to be tender is to be truly fierce” (44). Of course, many of the analysis I have discussed moves past the ideas of feminist criticism and uses deconstruction and even structuralism in order to make this argument cohesive and comprehensive. I do not think that feminist criticism alone can be used to discuss the gendering of terms, especially in pop culture today. Context, of course, is needed to understand the connotations surrounding the term “cowboy.”

Ehrlich, Gretel. The Solace of Open Spaces. New York, Penguin, 1985.

Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today. 3rd ed., Routledge, 2015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.