Finally, the reader is allowed to participate in the critical analysis of a text. However, the reader-response theory (outlined in Tyson’s textbook) is more complex than just analyzing how the reader (or you) feels about the text; in fact, there are a lot of formal considerations that go into making a successful reader response analysis. In Tyson’s chapter “Reader Response Criticism,” one of the types of reader response is affective stylistics. This category of reader response focuses on how the mechanics of the text shape reader response. Affect stylistics argues that “the text consists of the results it produces, and those results occur within the reader” (Tyson 167). I found affect stylistics appealing because it seemed to balance authorial intention—or the actual writer’s craft—with reader response and interpretation. Fish writes that affect stylistics should ask: “How does the reader of this sentence make meaning?” (167). Using textual clues, the reader can then make claims about the text and analyze how their reading experience was shaped by the text. While this technique of mapping “the pattern by which a text structures the reader’s response while reading” allows for active and close reading, I found that combining affect stylistics with social reader response would produce a more rounded argument (Tyson 168). Social reader response considers the “interpretive community” and evaluates how institutional assumptions influence the text (Tyson 176). If one were to combine affect stylistics with social reader response, they would produce an argument that not only looks to the text for structural clues but goes beyond the text to analyze historical or social context. Therefore, the reader response is a robust analysis of the textual craft and the social implications that surround the text. After reading about reader response, I still wonder whether it is the reader or the author who creates meaning—what came first, the reader or the meaning? Is the text completely reliant on a reliable reader to be interpreted and created into the meaningful analysis? Is there such a thing as reading for fun, or must there always be meaning and connection to the self?

Professor Charles’ essay “Meeting ‘Me’: Charles Dickens’s Moments of Self-Encounter” uses both affect stylistics and social response to craft a complex yet clear argument about Dickens. Reading her essay helped me understand how formal linguistics and stylistic choices help the reader close read and make meaning of a text. She active includes the reader into her critical essay and does so by setting up the reader response with close analysis of the text and sentence level. In addition, she addresses the reader’s responsibility to decode Dickens’s language and his social impacts on the culture at the time. Her evidence, which goes directly back to the text (affect) and the greater context (social response) continuously points towards the greater theme of reader experience and what kind of atmosphere Dickens is trying to create. Moving forward with my own critical analysis, I hope to combine affect stylistics with a social response.

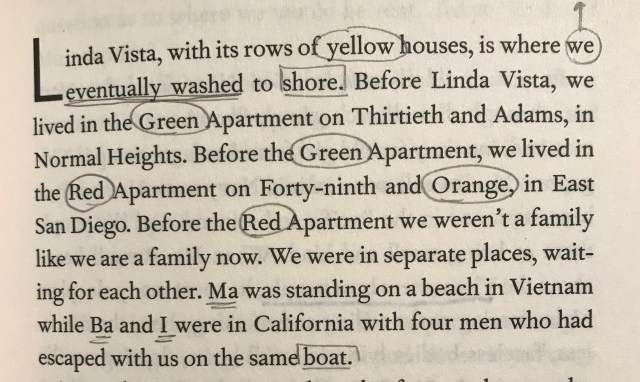

In Le Thi Diem Thuy’s novel The Gangster We Are All Looking For, Thuy begins the book with the following paragraph: (pg. 3)

Reading this text using an affect stylistic reader response, one would notice the repetitious use of colors to describe places, such as “yellow house,” “Green apartment,” “Red Apartment,” and “Forty-ninth and Orange.” This childish way of identifying places and the use of the past tense then leads the reader to believe that our narrator is a child looking back on her past experiences. Time and place are now established, but the textual analysis is needed to grasp what the text wants us to feel. The narrator withholds names, as she only gives pronouns for the first seven lines. The ambiguous “we” sets the reader up to believe that the “we” group was always the same, but “we” never stood for a complete family or group dynamic. Ma was across the water in Vietnam, and the child was with her dad and four men. This observational yet delayed response to her situation gives the reader insight into the narrator’s subconscious and way of processing information. We now know that this novel is going to first overload our senses, like with the colors, and then sneak in a blunt, but profound statement that changes our course of thinking and feeling about the previously mentioned sensory images. This contrast between image and statement speaks to the emotional and intellectual minds of the readers. Also, diction such as “we eventually washed ashore” implies that the journey was tiresome and that they washed up like debris. Using a social reading response, one would understand that immigrating to American from Vietnam was common in the 1970s and that the immigrant experience in America was not simple. The child narrator implies that she washed ashore as if she drifted there—unwanted by the Americans and far from home. Her life as a Vietnam refugee has just begun in this first paragraph, but the reader is keyed into cultural details about the immigrant experience. This reading now gives the readers context for why the child narrator may be describing locations in colors: because everything in this new world seems unreal and strange. Moreover, affect stylistics and social reader response can work well together to identify meaning from the language itself and the cultural context.

Works Cited

Lê Thi Diem Thúy. The Gangster We Are All Looking For. Anchor Books, 2016.

Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today. 3rd ed., Routledge, 2015

You must be logged in to post a comment.