The phrase in the title of this digital home for the Junior Seminar comes from Ralph Waldo Emerson. The action, “creative reading” is set in some sort of relation (is it also opposition?) to the phrase most people, certainly English majors, are more familiar with, “creative writing.” In his “American Scholar” address to the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Harvard in 1837 (as it turns out, Henry David Thoreau’s graduating class), Emerson says the following:

One must be an inventor to read well. As the proverb says, “He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry out the wealth of the Indies.” There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world. We then see, what is always true, that, as the seer’s hour of vision is short and rare among heavy days and months, so is its record, perchance, the least part of his volume. The discerning will read, in his Plato or Shakspeare [sic], only that least part, — only the authentic utterances of the oracle; — all the rest he rejects, were it never so many times Plato’s and Shakspeare’s.

Let’s begin to think about what “creative reading” could mean for us and what we will be doing in our Junior Seminar for English majors–we, scholars engaged in the critical study of literature. (A brief note on terminology: in Emerson’s day, “literature” included the study of what we now call English, as well as rhetoric, as well as philosophy, as well as the sciences. That’s an interest area in my scholarship; more later). We know what “creative writing” means and why we need to distinguish that act from what scholars do when they read Plato or Shakespeare. Or, I assume we know that, given the staying power of the phrase “creative writing.” However, I’m not sure that Emerson necessarily views “creative” the way we have come to understand the adjective. I get that sense from his attempt to define “creative reading” on the analogy of what he calls creative writing.

What’s the difference? What’s the relation or correlation between creative writing and reading? Whatever the answers are, I’d like to suggest that we will be exploring the relations and differences in this seminar. Our language, informed by our primary guide, Critical Theory Today, will be more recent than Emerson’s. But it will be similarly theoretical and critical. Indeed, Emerson argues against the assumption that theory or speculation is a bad thing. We will be using words to think about, reflect on, interrogate, and better understand how words are used in the books we read and the texts we study.

Let’s start with a kind of pre-test, before we know what we think and before we recognize the keywords and concepts you will have in hand by the end of the course and the culmination of your seminar project.

Question 1: How would you characterize Emerson’s critical approach to literature? What assumptions motivate his assertion of “creative reading”? What terms or critical methods (perhaps ones you have already encountered in your studies to this point) would you apply to Emerson, as similar as well as different from what he envisions for reading? In other words, how would you as a scholar (today) describe how Emerson conceived the work and character of the scholar?

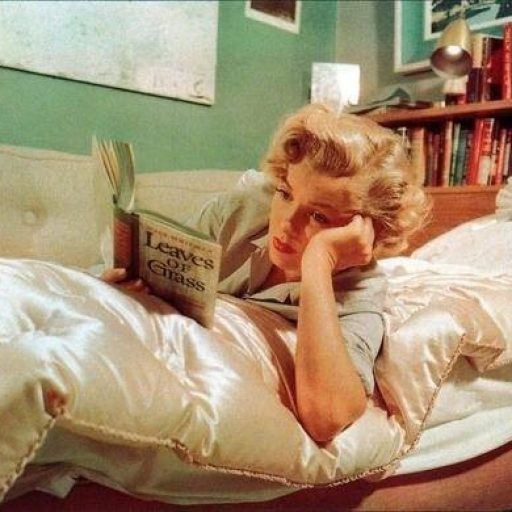

Question 2: If we were to pursue a critical reading of the text that serves as the header image for our syllabus, the image of Marilyn Monroe reading Walt Whitman (a real image, as it happens; favorite authors included Whitman, Joyce, and Ellison), what could we do with it and what could we say about it? What critical/theoretical approaches might this text invite?

Consider another image which imagines Whitman reading Emily Dickinson. What kinds of critical and theoretical ideas do these images assume or embody? What does that question mean? Stay tuned.

You must be logged in to post a comment.